Why Mentoring?

Women who have a mentor can advance more quickly, and to higher levels, than those who are not supported.3

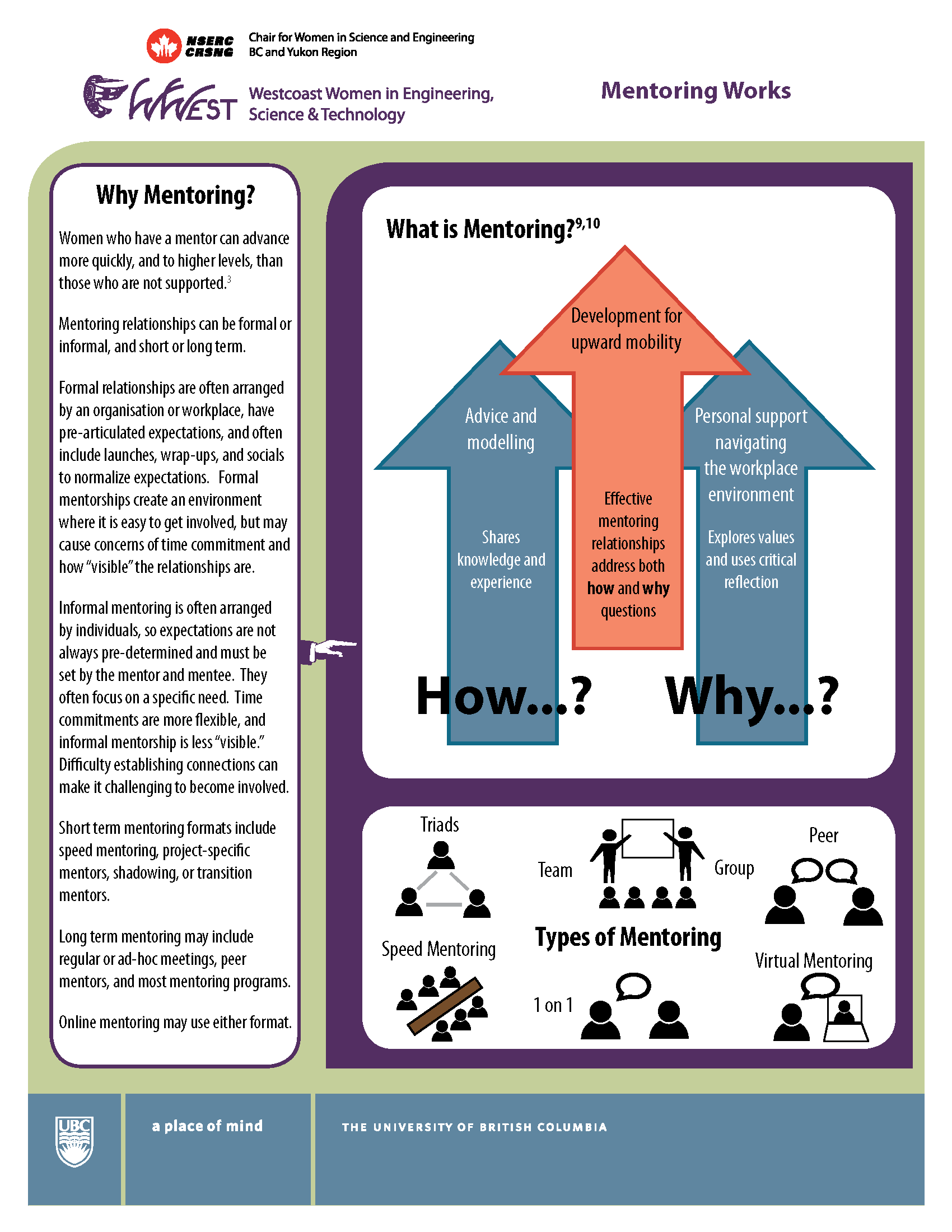

Mentoring relationships can be formal or informal, and short or long term.

Formal relationships are often arranged by an organisation or workplace, have pre-articulated expectations, and often include launches, wrap-ups, and socials to normalize expectations. Formal mentorships create an environment where it is easy to get involved, but may cause concerns of time commitment and how “visible” the relationships are.

Informal mentoring is often arranged by individuals, so expectations are not always pre-determined and must be set by the mentor and mentee. They often focus on a specific need.

Time commitments are more flexible, and informal mentorship is less “visible.” Difficulty establishing connections can make it challenging to become involved.

Short term mentoring formats include speed mentoring, project-specific mentors, shadowing, or transition mentors.

Long term mentoring may include regular or ad-hoc meetings, peer mentors, and most mentoring programs.

Online mentoring may use either format.

Mentoring at Work

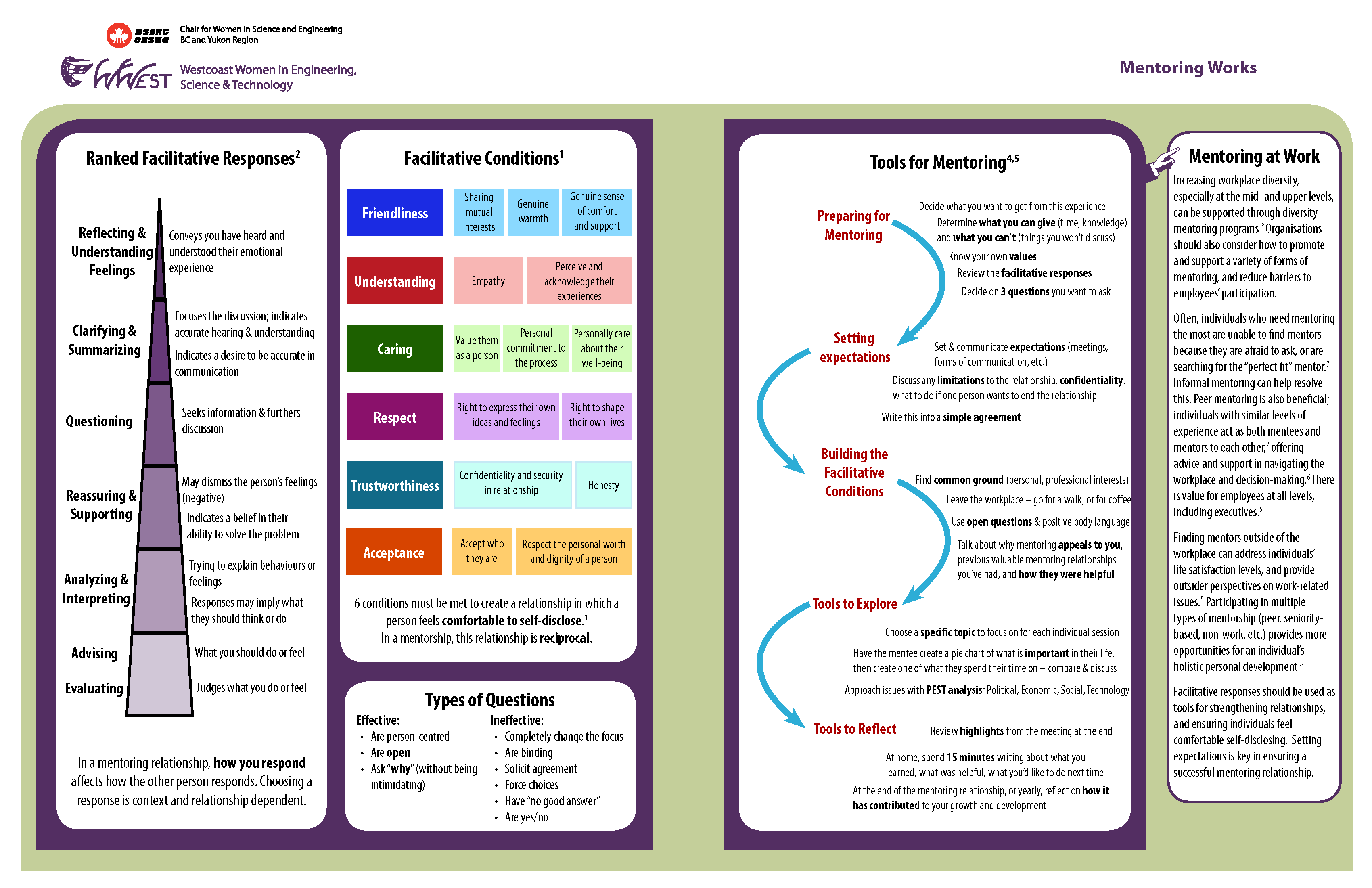

Increasing workplace diversity, especially at the mid- and upper levels, can be supported through diversity mentoring programs.8 Organisations should also consider how to promote and support a variety of forms of mentoring, and reduce barriers to employees’ participation.

Often, individuals who need mentoring the most are unable to find mentors because they are afraid to ask, or are searching for the “perfect fit” mentor.7 Informal mentoring can help resolve this. Peer mentoring is also beneficial; individuals with similar levels of experience act as both mentees and mentors to each other,7 offering advice and support in navigating the workplace and decision-making.6 There is value for employees at all levels, including executives.5

Finding mentors outside of the workplace can address individuals’ life satisfaction levels, and provide outsider perspectives on work-related issues.5 Participating in multiple types of mentorship (peer, seniority-based, non-work, etc.) provides more opportunities for an individual’s holistic personal development.5

Facilitative responses should be used as tools for strengthening relationships, and ensuring individuals feel comfortable self-disclosing. Setting expectations is key in ensuring a successful mentoring relationship.

References

1. Myrick, R. D. (1987). Developmental guidance and counseling: A practical approach. Minneapolis, MN: Educational Media Corp.

2. Wittmer, J. & Myrick, R. D. (1980). Facilitative teaching: Theory and practice. (2nd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: Educational Media Corp.

3. Cukier, W., Smarz, S. & Yap, M. (2012). Using the diversity audit tool to assess the status of women in the Canadian financial services sector. The International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations, 11(3),15-36.

4. Zachary, L. (2009). Make mentoring work for you: Ten strategies for success. T + D, 63(12), 76-77.

5. Zachary, L. & Fischler, L. (2009). Help on the way: Senior leaders can benefit from working with a mentor. Leadership in Action, 29(2), 7-11.

6. Murphy, W. M. & Kram, K. (2010) Understanding non-work relationships in developmental networks. Career Development International, 15(7), 637-663.

7. Zachary, L. (2010). Informal mentoring. Leadership Excellence, 27(2), 16.

8. Clutterbuck, D. (2012). Understanding diversity mentoring. In Clutterback, D., Poulsen, K. M., & Kochan, F. (Eds.), Developing successful diversity mentoring programmes: An international casebook (pp. 1-17). New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

9. Kram, K. E. (1985). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

10. Bozeman, B. & Feeney, M. K. (2007). Toward a useful theory of mentoring: A conceptual analysis and critique. Administration & Society, 39(6), 719–739.

Recommended Readings

1. Bachkirova, T., Jackson, P., & Clutterbuck, D. (Eds.). (2011). Coaching and mentoring supervision: Theory and practice. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

2. Clutterback, D., Poulsen, K. M., & Kochan, F. (Eds.). (2012). Developing successful diversity mentoring programmes: An international casebook. New York: McGraw-Hill

Education.

3. Clutterbuck, D. (2012). Coaching and mentoring in support of management development 1. In Armstrong, S., & Fukami, C. (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Management Learning, Education and Development (pp.477-497). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Copyright notice

Copyright © WWEST 2013

This material may be distributed for free, but must include WWEST’s branding.

It is available for co-branding, please see our co-branding page for more information.